Can Amazon wean us off paper?

Amazon hopes its ebook reader will do for books what the iPod did for music. Danny Bradbury assesses this novel new device

GALLERY:The history of ebooks

- The Guardian

- Thursday November 22 2007

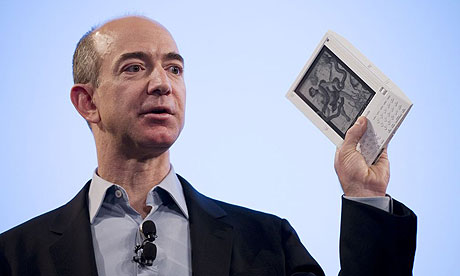

Jeff Bezos, founder and CEO of Amazon, shows off the new Kindle ebook reader in New York

Jeff Bezos was, as usual, in ebullient form on Monday as he launched Amazon's much-rumoured "Kindle" ebook device: "we knew we would never out-book the book," he explained. "We would have to take the technology and do things the book could never do." Certainly, it may do some of those things: with a battery life of up to 30 hours and a two-hour recharge, it is designed to untether readers from the power socket, like a regular book. But the $399 (£194) device will do more than traditional books ever could.

The US-only mobile network connection lets users instantly receive newspapers and magazines subscribed to via Amazon, and displays documents that you send to a personal Kindle email address (for a 10-cent charge). But almost as soon as it appeared, bloggers and testers began to find wrinkles they weren't so sure about: the format is proprietary (so no reading it on your PC), you have to pay to read blogs or papers that are free online, and the 170 dot per inch screen isn't as bright as real paper. Is the Kindle an iPod for books - or just another flawed idea?

Earlier trials

Ebook readers already have a long and unsuccessful history. Sony's e-Reader, available only in the US, is a revamped version of an earlier version trialled in Japan, while the UK distributor for Dutch e-reader vendor Irex estimates that at most, 10,000 units of its iLiad device have been sold worldwide. But Amazon knows books, and it knows technology, and it has significant muscle in both. Could it go further?

Jeff Jarvis, the Guardian columnist and journalism professor at the City University of New York, isn't excited about the Kindle; he's saving his pennies for an iPhone. "Is it the perfect thing for reading a 30,000-word book? No," he says. But he already carries a camera, an iPod, a Mac and a phone, and is gradually consolidating. He prefers a single device that can do many things adequately rather than a gaggle of bulky dedicated gadgets. "The beauty of the iPhone is that it has a browser, and I read a lot of things in browsers," he says. "I really don't want to carry around another device."

Should we make space for a dedicated e-reader or make do with a generic device? While dedicated readers have come and gone, others have tried to shoehorn ebooks onto PCs and mobile phones. Jane Tappuni is one of them. Her company ICUE (i-cue.co.uk) started out publishing ebooks on tiny mobile phone screens. Words would flash on to the screen one after the other in quick succession, in a system advocates call "flash reading". As screens evolved, she began offering other formats including a screen ticker and a normal page view. But customers aren't buying as fast as she'd hoped.

"Convergence devices are becoming so easy to read from, and so good," says a defiant Tappuni. "I can't see that many people would spend £200 on a dedicated reader." But clearly, they'll spend big bucks on an iPhone, which could finally give her business what it needs. With Apple opening the platform up to third party developers, she hopes to ship an ICUE reader for it. Don Norman, co-founder of technology design consultancy Nielsen Norman Group, thinks she's backing the wrong horse. "Will people read stuff on the iPhone? Sure. But it's not good for that," he warns. Instead, he thinks ebook readers should be dedicated because it will make them simpler to use and less expensive.

They're also more enjoyable to read from, says Peter Blanchard, who runs Libresco, UK distributor for Irex's dedicated e-reader. "The size of an iPhone isn't in any way comparable to the size of a paperback book," he says. "And the difference between reading on a backlit screen and the iLiad is that [on the latter] the reading experience is as close to paper as makes no difference."

But if an associate professor like Jarvis is unwilling to carry a dedicated reader around, who will? Book-laden school students, say some. Others suggest lawyers and other professionals who need access to lots of documents: the legal publisher Sweet & Maxwell converted two of its titles to one of the iLiad's supported formats, and tested the device with some customers.

"Lawyers have to lug around huge tomes," points out publishing manager Chris Hendry. "One guy was smitten with it. He uses it all the time and didn't want to give it back." But not everyone was enamoured. One person was perfectly happy looking up reference material on his laptop computer, while another was frustrated by the startup speed and the sub-second delay when turning a page on the device, Hendry says. Another couldn't cope with keeping the battery charged, and couldn't update the software. These people should be the perfect market for dedicated e-readers, but "we have concluded that it is between two and five years away", Hendry says.

Other publishers worry that the whole ebook concept is flawed. Like many, HarperCollins is currently in the throes of digitising its content. "We're partly digitising because we are saying that we're not as interested in the book as a content delivery mechanism," says group digital publisher Clive Malcher. "We want to start with the content and deliver it in the most appropriate medium."

Searching for a standard

"The book is a broad type of technology rather than a product, and we need to talk about product," says Matt Hunter, global practice leader for consumer experience design at international design firm IDEO. For him, products include novels, newspapers and reference titles. If those multiply and diverge, e-reader vendors could find it hard to support them all. Even publishers are not yet sure what the products will look like or how we'll consume them. How many radio pundits had thought of the podcast before the MP3 player appeared?

The evolution of e-reader software and the formats used to encode the books shows us where this may go. Adobe now offers a software-based ebook reader called Digital Editions that supports ePub, an electronic publishing standard that most interested parties seem to be getting behind. ePub lets publishers add their own objects to a document, explains the general manager of Adobe's digital publishing business, Bill McCoy. The company's reader supports interactive animations and video clips in its own Flash multimedia format, and is also leaving room for features such as social networking (virtual book clubs, anyone?). It also reflows content for screens of different sizes, emphasising the drive to stay device-independent.

With publishers and format developers so heavily focused on content and less interested in conventional notions of the book, developing a dedicated unit designed to replicate it begins to look either brave or foolish. Wouldn't a generic device be more adaptable?

Accepting that the content will never stand still suggests that the hardware and software won't either; that the iPhone isn't the perfect e-reader, and neither is the Kindle, or any of the others. "There's always something better coming down the pipe," argues Hunter.

Biggest challenge

In any case, developing the perfect reader won't be the biggest challenge for the still-tiny ebook industry. John Maxwell, an assistant professor in the master publishing program at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, points to digital rights management and content sharing as the bigger challenge.

"We watched the music industry slouch towards a non-DRM MP3 format," he warns. Watching the battle over music downloads, IDEO's Hunter has told clients that even though they want to make money from their digital assets, they can't. "There is no intrinsic value in the media itself. It's in the exchange," he says. "It's so hard for an industry to hear, to listen and to understand when significant disruption is happening."

Book publishers may baulk at the idea that books have no value (Amazon certainly won't stop charging for them), but they should acknowledge that at least part of that value is shifting.

Before we ask which electronic text reader is better, we should ask what consumers want. How easy do the devices make it to get the content in the first place, and to put it on to the device? How easy is it to lend books to each other, which for many is one of the most enjoyable aspects of reading?

Failing to answer questions like these may make it even harder to wean readers away from paper. To make ebooks work, we have to take user-friendliness in the device as a given and then look for it in the business model - which is why the fortunes of Amazon's Kindle will depend on much more than the hardware alone.